In this article emerging social practice artist Toni Hassan explores how art – in many forms – can cathartically engage climate grief. Toni produced collaborative work about Australia’s Black Summer that provided testimony and space for lament.

The fierce bushfires that engulfed the eastern seaboard in 2019-20 had real impacts at so many material and spiritual levels but at its most basic on the body and breath. I felt it as a person with asthma.

My city of Canberra was enveloped in toxic smoke and later struck by a devastating hailstorm. It was then that my sadness about a warming planet moved into deep melancholy.

(Since the Black Summer fires, of course, we have seen devastating floods across the Northern Rivers of NSW to greater Sydney).

I asked myself, ‘how can I make art that cathartically engages my climate grief?’

Initial research, as part of my Honours year at the ANU School of Art and Design, fed a social art project that bore witness to Black Summer and affirmed the role and potential of collaborative arts for public bereavement and shared hope.

What did I set out to do?

I began by reading eco-philosophers Joanna Macy and Charles Eisenstein, writers and experiential thinkers grappling with their own eco-grief. In the art theory world, I read the scholarly work of Clare Bishop. Her definitive book on participatory art is full of examples from the mid-20th century of art engaging social realities. Equally seminal is the writing of Grant Kester. His book Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art looks at the creative power of facilitated dialogue and exchange. From that I took my cue.

BREATH DONATIONS AND DIALOGUE

I set out to create my own Conversation Pieces; interviews with women in the capital region who had been through Black Summer. In our recorded one-to-one conversations, I began with a breathing exercise, recording the ebb and flow of breath. I then asked the women about the impacts of that season on their bodies and on their breath. I took photographs of participants in ways that reflected the impact .

The stories as transcripts and voices became ‘warm’ data that inspired aesthetic responses.

The dialogues avoided polemic or didactic questions, but returned to the subjective experience of heat, smoke and the temporal.

Women were asked what that summer did to their sense of time. I asked, if their lungs could talk, what were they saying?

If they could talk they would be screaming, “I’m in pain, stop, stop, stop, I am in pain!” My body and my mind just couldn’t handle it all. – Aoibhinn Crimmins.

The women told me they found some release and revelation talking about that time. Me too. It felt shared. I became conscious too, of not wanting to give anyone a grief hangover, stirring things up for its own sake; that I felt responsibility to listen as positive care. A theme emerged that connected environmental damage with violence against women.

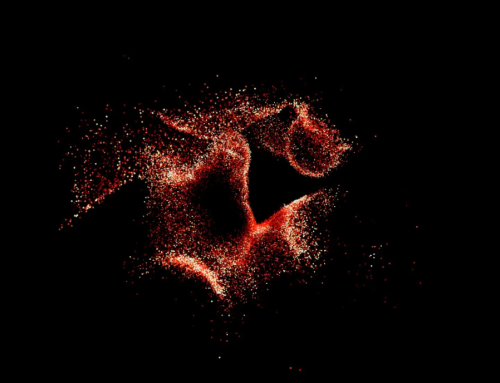

Photograph: Untitled, from series Body and Breath series, 2021

VIDEO STORIES

I sampled a selection of the conversations for short videos, using meditative movement to create new constructions of meaning. In one of them, the Australian flag moves and dances against a clear blue sky, as if in response to human breath and voice. The flag – an object full of loaded and unresolved issues – tests the viewer’s own relationship with the object. The voice one hears belongs to volunteer firefighter, Rhian Williams:

I just remember being staggered by days and days and days and days of smoke, and not being able to see the sky and it felt like the end of the world. It felt like, just this total sense in that moment, of feeling totally powerless and a reminder that the only thing that was going to stop those fires last year was rain.

LARGE EXPANDED PAINTINGS

I also produced acrylic paintings on large recycled curtains that were hung like tarps as a kind of temporary and emergency shelter; ‘unhomely homes’.

In Refuge the helicopter references the spark that sent Namadgi National Park in flames. Several women in Conversation Pieces were most distressed by news of the loss of Namadgi. An endangered black cockatoo glides across the scene.

“Refuge” (from Shelter series), 2021. Acrylic on recycled curtain, eyelets, rope and rocks. 130 x 210 cm (with dimensions variable as an installation)

DIALOGUES IN PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: LAMENT AS CONTEMPORARY ART

For the final work I planned to bring the women together – to give back and consolidate new and existing friendships, and to share with a wider audience their profound observations. I planned an event on City Hill in Canberra, a symbolic place looking south towards Federal Parliament House; as a kind of declaration and testimonial. A COVID lockdown turned it into an online event – a virtual public lamentation.

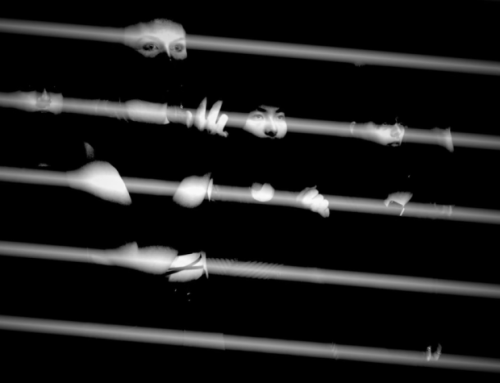

Performance art is thought of as first and foremost a visual experience. It is not acting but sees the performer suspend her conditioning. It is a one-off. I settled on a lamentation that would be semi-scripted and with some props in collaboration with musicians (who generously volunteered their time) whose instruments could register the mood of extracts from Conversation Pieces.

This was an experiment with sound and my body (with all its vulnerability) as the key medium. It was not theatre but a civic ritual that created space to bring and process complex experience.

I rubbed charcoal onto my face and wore hessian to represent grief and poverty – borrowing from the Jewish mourning ritual of sackcloth and ash. I used gestures, the physical language of lament, such as kneeling with my head bent towards the earth.

The lamentation aimed to move the problem of climate change from the abstract to the embodied, creating space to negotiate what people bring to it with their own bodies.

The audience – about 100 people online – shared and represented the physical manifestation of my expressed grief. The feedback I received, with the immediacy of Zoom chat, affirmed its value. A viewer wrote: It was a beautiful and devastating piece. What I felt in my body was profound grief…And I take on board the message of love to overcome fear. Let us celebrate that.

Still image from 45 minute live performance “Black Summer Lamentation on City Hill”, September 12, 2021.

ENGAGING THE HEART

Most expressions of grief are private. Bereavement practice is typically about the death of a loved one or unexpected deaths in a disaster. This is new territory in that climate change is here and more adverse weather events are expected. Climate grief is not just personal but has broad social dimensions for communities and nations. Still, research by the psychological profession on this is in its infancy.

Facilitated dialogue that engages the sensors and the public act of lament, I believe, are well suited contemporary and collaborative forms to accompany the planet’s climate transition. I have learnt a lot to inform a potential hybrid practice.

The work actualised my own experience of Black Summer and resonated with others who lived through that time too.

It has deepened my view that one of the challenges for artists and communicators is making climate change culturally meaningful to peoples’ own social realities, bringing empathy and allowing room for soft discourse about climate change.

The arts can help move the subject beyond the limits of official discourse, partisan politics and scientific data. It helps engage the head and the heart.

—

Toni Hassan is a writer, advocate and an emerging social practice artist. She is a founding member of the Women’s Climate Congress. Conversation Pieces is also now available as a book. Order by email: toni.hassan.art@gmail.com