Jennifer Blau is a photographic artist and art therapist interested in the emotional landscape and therapeutic possibilities of photography. Jennifer works at the intersection of art, psychology and documentary photography. Her work explores story and identity in people who may be marginalised or experiencing challenges in life.

In her latest work ‘Patricia’s Room’, Jennifer explores the onset of dementia through a series of intimate portraits of her 90-year-old mother-in-law, in order to shed light on a subject she describes as “laden with stigma”. The work ‘Forget me Not’ from the series was recently selected for the National Photographic Portrait Prize. The Patricia’s Room series is also currently being exhibited in Head On Photo Festival on display along the Bondi Beach Promenade until the end of January.

“Forget Me Not”. Beautiful, elegant and engaged, Patricia defied the stereotype of a woman at 90. In Western culture, we rarely turn our cameras on the elderly, rendering them invisible, especially as they decline. Patricia was surprised I considered her a worthy subject, and said she was “amused to be my muse”.

How and why did you develop the idea for this moving and personal project and what does it mean to you?

Patricia is my mother-in-law and I began photographing her as she approached ninety. I hoped to build on my previous work, The 50 Book: Women Celebrate Life, exploring how women over 50 are often made to feel invisible as they age, despite wisdom, experience and other positive qualities. Patricia was beautiful, elegant and engaged and defied the stereotype of a woman at 90. I wondered how she viewed herself and wanted to document that.

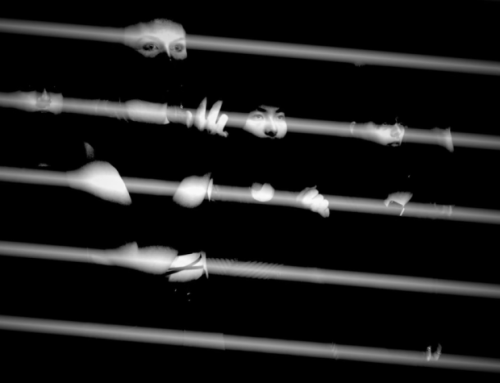

But before long, she began to decline. A major heart operation had triggered increasing confusion and memory loss and Patricia was diagnosed with dementia. This really changed my focus and raised new questions. What happens to your sense of self when you lose your memory? How might you feel and how might others view you? What happens when you lose sense of time, place and relationships? As a photographer and art therapist I wondered how I might portray and understand this life experience?

I knew a bit about dementia already having sadly lost my mother to Alzheimer’s disease, and I have worked with dementia patients in nursing homes as an art therapist. I know how devastating it is. Furthermore, there are almost half a million Australians now suffering from dementia and it’s the leading cause of death for women. Most people have a family member or know someone affected. I wanted to shed light on a subject laden with stigma, while at the same time exploring Patricia’s experience with an empathetic eye.

Did using photography as an art form to explore the theme offer you unexpected insights?

As Patricia’s eyesight and hearing began to break down along with her memory and cognition, her world became increasingly less tangible. I wanted to find a new visual language to reflect the sense of fading, blurring, disorientation and invisibility she experienced. A sense of being here – yet, not quite here. So I began researching and experimenting with various ways to reflect this. Photography was a perfect medium — by its very nature it’s about capturing a moment in time and in space, yet it allows us to play with the way in which these concepts are rendered. Interestingly, I also found that experimenting with different ideas helped articulate feelings that I hadn’t been aware of.

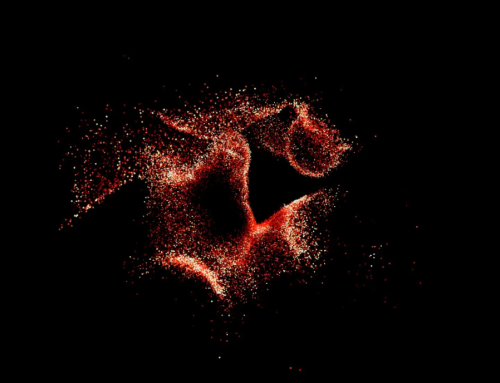

“Ageless”. At 90 with dementia, Patricia became ageless. Although unable to remember moments in the short term, long-term memories remained clear. Having lost sense of time, she would move between eras, thinking she was 40 one day, 60 the next. It reminds us that we are only as old as we think we are, and our younger self is always a part of us.

What role did the project play on Patricia’s mental and physical well-being?

The project coincided with the first Covid lockdown in 2020 and so she soon became confined to her home, often anxious and lonely. I live next door to her so was able to visit her often. Photography became a wonderful activity for us as well as a way of connecting with her as she lost words and struggled with conversation. Our portrait sessions became a kind of affirmation as she dressed and posed for the camera. She’d often thank me and say how surprised she was that I considered her a worthy subject — she was “amused to be my muse”.

One of the important things with someone with dementia is to spend time reminiscing and so we went through her family albums and talked about her life. Having lost sense of time, she’d move between eras, thinking she was 40 one day, 60 the next, at times a little girl. It reminds us that we’re only as old as we think we are, and our younger self is always a part of us. So I began to also look for ways to incorporate this into my portraits of her.

One thing that cut through the haze of Patricia’s dementia was music. In photographing her playing the piano, she appeared transported to another realm. She could remember how to play and sometimes sing along. In music and art therapy, we know that sensory experiences activate different parts of the brain that can stimulate memory and make a person come alive. It’s amazing that although recent memories fade, music remains.

There are many ways in which documentary photography and therapy interweave. With any documentary photography project, it is important to develop a relationship of trust with whoever you photograph so that they can accept your presence, relax and not perform for the camera. Likewise in therapy, we also focus on creating a non-judgmental, safe space of trust. We talk about ‘holding space’ for a client — meaning we’re physically, mentally, and emotionally present to support someone as they feel their feelings, allowing them to be seen and heard fully. And I think this quiet process of photography with Patricia was similar. She allowed me to be there and simply accept and witness her as she is, and she seemed comforted by my presence.

“Vestige”. Along with her memory, Patricia’s eyesight and hearing began to deteriorate. Our senses are how we perceive the world, and as they fail, the world becomes less tangible. Patricia’s presence in it was fading. But the more she began to slip away the more I wanted to capture her beauty in all states of being.

How was your relationship with Patricia affected by the process of documenting her experience using photography?

The process became a way of more deeply understanding her and I think that it certainly helped develop a more empathic relationship. Although I already knew her well, such close observation of her over multiple shoots and edits really made me begin to inhabit ‘Patricia’s Room’.

Nevertheless I was always anxious about the responsibility of the power balance between photographer and subject, about whether with dementia she could really understand and approve of the work, and about presenting someone so close to me in such a vulnerable way. At times I worried that I might be betraying her trust, taking advantage of the fact that she enjoyed our sessions as I experimented with different techniques to represent how I perceived her experience. Were the images representing her voice or mine? Was this how she wanted to be seen?

But of course what we shoot is so often a reflection of ourselves. So ultimately I came to realise that this is as much about my story as hers: perhaps a projection of my own vulnerabilities about ageing, mortality and loss. I’m not alone with those feelings and recognise that dementia is not only about the person who has it but the family’s response, too.

As long as the relationship remains respectful, I think there are benefits to us all in sharing stories of vulnerability. It helps build understanding and compassion, and can resonate with others with similar experiences, helping everyone experiencing not feel so alone.

“Transported”. One thing that cut through the haze of Patricia’s dementia was music. She appeared transported to another realm as she played piano, or listened to a CD. Music offered connections with her family and her past, eliciting clear memories and strong feelings. Although recent memories fade, music remains.

What role do you feel the arts can play not only with someone’s personal experience with dementia, but also in our societal perception of ageing?

Art has the capacity to move us and inspire us, as well as ask questions. It also allows us to encounter difficult life experiences at a distance and offers a safe way to begin to acknowledge some of our fears. So often people simply don’t know what to say when someone has a terrible diagnosis such as dementia. They don’t have the words to talk about it and it’s scary, so it’s easier to turn away and pretend it’s something that only happens to others. The person concerned becomes isolated and the carers often do, too. But sadly dementia is something that will affect all of us at some point and we need to talk about it and find better ways to support each other.

More broadly, it’s important that we use the arts to challenge negative perceptions about ageing because this not only plays in to how people feel about themselves but how as a society we value and treat older people. If people are made to feel worthless and invisible (as is so common in Western culture) they lose confidence, a sense of purpose and become disengaged, isolated, and often depressed. It’s a downward spiral and that’s a huge burden for everyone. It’s also a waste of enormous potential older people have to contribute wisdom and experience. The arts help us to open a dialogue about that.

How would you like to see the arts developed in the context of ageing and aged care? What can the arts do to improve personal, clinical and more broader care and understanding?

I’d like to see more focus on using the arts to promote positive ageing from middle age onwards. The arts have the potential to empower older people by giving them a voice, a new means of communicating and possibly a new way of thinking about themselves. The arts keep us connected and make sense of our experiences, both individually and collectively.

I think we can look at art in aged care more broadly than we do. Arts and crafts can be enjoyable activities but we have the potential to also incorporate more psychological support via art therapy led by professional art therapists alongside other health professionals. Art therapists are highly trained at postgraduate level in art and in counselling and psychotherapy and their expertise is often unrecognised.

What areas interest you for further exploration as an artist and therapist?

My portrait photography remains a focus for exploring the human condition and hopefully encouraging more respect and compassion for others. I’ve worked with people experiencing homelessness, trauma and mental health conditions, including a project raising awareness about eating disorders for Way Ahead Mental Health Association. However much of my work has had a focus on exploring ageing and I’d like do more of that and incorporate it within art therapy, too.

I’m also passionate about ecotherapy and how time spent in nature can improve our mental health and wellbeing and incorporate this in my own photography practice. I also offer mindfulness-based photography and art workshops in nature to reduce stress, anxiety and promote self care within my Art of Wellbeing practice. Incorporating mindfulness and meditation, the workshops invite people to use their phone cameras to slow down and connect with nature, as well as stimulate further creative processes. I find photography is a great way to help people overcome fear about not being good at art or staring at a blank page. I offer bespoke groups for organisations and the community.

Click here for a direct link to the project on Jennifer’s website: https://www.jenniferblau.com/documentary/patricias-room

Jennifer Blau. Photo credit Bettina Cutler.

jenniferblau.com

Instagram @jenniferblauphoto

Instagram @jenblau_artofwellbeing

Instagram @the50book

Facebook @the50book

Feature image: “On Refection”. Forever beautiful, Patricia lies on her bed in what seems a moment of quiet reflection. I can only wonder what she is thinking and feeling. I know she is comforted by my presence and I feel privileged to be there to witness the moment.

Interview and post by Ian Thomson